Can democratization through technology-based decentralization finally become reality?

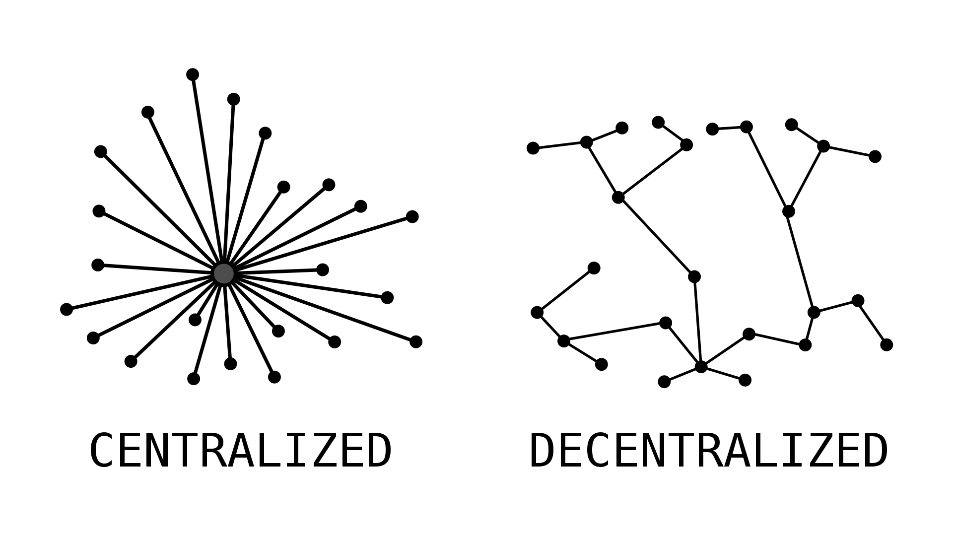

Then and now, the emergence of technologies seems to be accompanied by an astonishingly repetitive narrative of promoting democracy through decentralising power, knowledge or means of production. Supporters thereby often refer to John Naisbett, who already in 1982 made the claim that social decentralization would be one of ten ground-breaking megatrends. Expressed more abstractly, social decentralisation describes a condition under which the actions of a multitude of agents are coherent and effective and still do not rely on a reduction of persons who are capable to directly and effectively act. This idea can be found in a broad spectrum of social theories about decentralising power, knowledge or means of production through technologies: Theories on blockchain-technology or 3D-printing for instance often emphasize individualism, market-libertarianism and anti-statism. Theories on vertical-farming or solar-energy for instance are in turn rather animated by an ideal of “green” localism, i.e. cooperative economy, anti-globalization and low-threshold participation.

Unfortunately, as the development of the Internet illustrates, hopes of salutary decentralization can surprisingly quickly turn into their drastic opposite. Early enthusiasts celebrated the Internet as a democratic „great equalizer“ among citizens and between state and citizens and perceived it as promoting political deliberation while eliminating the necessity of mass-media and excessive central authority. Nowadays however, observers assert the Internet’s high degree of compatibility with autocratic regimes, given the extensive possibilities for surveillance and centralized storage of data and knowledge. But is the idea of promoting democracy through technology-based decentralisation thus hopeless? My answer is: theories of technology-based decentralisation provide a good example of putting the cart before the horse. It perhaps depends more on its realization then on its technical features whether a technology actually develops its hoped-for democracy promoting potential.

How exactly is technology-based decentralisation supposed to promote democracy?

But first the basics: How is technology supposed to promote democracy? Ideationally, democracy may be defined as a form of governance in which people meaningfully participate in decisions which affect them and other members of their group. Democratic institutions shall thereby provide equal opportunities for everybody, for example protection against the domination of a small number of powerful agents. When this is given, “civic intelligence” may emerge, i.e. democratic processes would represent good decisions when it comes to addressing essential issues while being fair to potentially affected people. In the best case civic intelligence would be able to learn, remember and reflect – almost like other forms of intelligence. However, according to political philosopher Joshua Cohen, this depends on whether decisions originate from a free, reasoned, equal and consensual deliberation. Hence, among other characteristics, governmental transparency, shared and diverse knowledge, social capital, relative economic equality and open and diverse information and communication systems are fundamental for democracy. At this point, theories which stress the democracy promoting potential of particular technologies come into play.

The proponents’ argumentation of democratization through technology-based decentralisation may thereby roughly be divided into three steps: First, new technologies enable the replacement of centrally coordinated communication, transaction, means of productions or decision-making by more dispersed peer-to-peer-networks. Second, the importance and significance of the respective established intermediary organisations and the social hierarchies they impose will in order diminish. Lastly, these dynamics will lead to significant reductions of power and information asymmetries, intransparency and inequality overall and will thus promote democracy and civic intelligence. Moreover, decentralization would enforce an architectural guarantee against coercive centralized exercise of power and systemic crises. In summary, to paraphrase Langdon Winner: technologies which require centralisation and thus potentially undermine democracy and civic intelligence become obsolete and are replaced by technologies which are more compatible with a rather deliberative comprehension of democracy.

It’s more than just a fix!

Apparently, the theories on democratization through technology-based decentralisation are not just about technological fixes for single shortcomings of democracy. They rather constitute a far more comprehensive socio-technical imaginary. This concept developed by Sheila Jasanoff describes collective visions of desirable futures which are animated by a shared understanding of social life and social order. These imaginaries are socio-technical since they are inspired by scientific and technical change and at the same influence technological progress by blazoning it with their words and visions. Framing those theories as socio-technical imaginaries actually allows to reflect whether and to whom this societal future appears worthy of being achieved.

Especially noticeable are the inauspicious simplifications which often accompany socio-technical imaginaries and probably foremost serve their supporters. First, decentralization imaginaries present technologies as catalysts for a fully-fledged decentralised substitution of an “outdated” contemporary social context. The technology thereby becomes decoupled from its socio-economic context. Accordingly, 3D-printing will fully replace the industrial sector and decentralised solar energy is making large, centralized power plants completely obsolete. However, should this actually materialize, those who depend on the "outdated" social contexts would probably have the highest transition costs. Perhaps one would feel more sympathy for factory workers than for the shareholders of a nuclear power station. But in both cases, the democratic opposition to these "democracy-promoting" technologies is certain. Second, socio-technical imaginaries of decentralisation tend to social overgeneralization. This means that supporters, who often belong to a very specific user milieu, tend to infer their habits and capabilities to an entire population. But there are expectable differences in competences. Consequently, even if technology-based decentralisation succeeds, maintaining or even improving the accustomed standards with decentralised technologies may be significantly easier for some groups or individuals than for other. The hoped-for higher self-efficacy of some individuals and groups may be thus accompanied by an even higher level of inequality. Third, from a temporal perspective, it would be hence in the supporters’ very best interest to keep the imaginary of democratization through decentralisation alive as a "proximal future": no previously failed attempt of realisation would suffice to prevent them from repeatedly announcing its imminent fulfilment. Instead, the imaginaries would afterwards be simplified at important points for the sake of coherence.

But what can be done better?

Is there still hope for those theories? At least, it is possible to learn from technologies that have been successful or failed in democratization through decentralisation in the past. By doing exactly this, analysts lately called for expanding “participatory design” in order to unfold the real potential of democratization through decentralisation.

Participatory Design can be best understood as an approach to involve users, designers as well as the technology itself in the process of technological development. Participatory design thereby anticipates the well-considered common good at all stages of a technologies’ development and includes public dialogue in its implementation. Concrete considerations for applying this concept on technologies for the sake of decentralisation are for example:

- Historical Impacts: Researcher as well as designers should analyse how technologies which belong to the historical strand of decentralisation imaginaries impacted different groups in the past. This also means to ask what alternatives to past harms could have been possible, how new technologies of an imaginary could even rectify past damage and how imaginaries could be reformed on that basis: Can old dreams of e-democracy, which have attracted attention because of their high manipulability for example eventually be revived by blockchain-supported elections?

- Design of the Stack: Designers and researchers should extend their scope and examine imaginaries at all layers of the technological stack. This means that basic technologies and infrastructure which are required to realize a certain technology should be analysed in order to understand the underlying power dynamics. For instance, what is the point of decentralized solar energy if it is still fed into a centralized power grid?

However, as this extract of suggestions already shows, it is not necessarily the technology that conjures up the desired future by itself. Instead, already the emergence and design of technologies should meet high democratic standards to unfold a technologies’ potential of promoting democracy. Since this is probably only possible in an already extensively democratized environment, the hoped-for impact of the supposedly democratizing technologies is not by any means certain.